THE POSSIBLE FUTURES OF A SMALL AUSTRALIAN RURAL SHIRE:

AN EXAMPLE OF SCENARIO PLANNING

Some years ago I was involved with a scenario planning project to help a small rural Australian local government area think about its possible futures.

The name of the actual town has been disguised as “Littletown”.

This is a summary of some of the report.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

SUMMARY OF THE DOCUMENT

This document is in seven chapters.

Chapter 1 provides an overview of the document and some general comments on the nature of change.

Chapter 2 examines the technique of scenario planning and explains how the fours scenarios in the following chapters were arrived at.

Chapter 3 provides an introduction to the following four scenarios.

Chapter 4 describes “Back to Nature”: a Littletown in which there is high environmental protection and little economic growth.

Chapter 5 describes “Green Littletown”: a Littletown in which there is both high environmental protection and high economic growth

Chapter 6 describes “Ghost Town”: a “Littletown” in which there is both low environmental protection and low economic growth.

Chapter 7 describes “Brown Littletown”: a “Littletown” in which the environment has less priority than the generation of high economic growth.

THE NATURE OF CHANGE

Never “Relaxed and Comfortable”

Life nowadays never reaches a plateau, a comfortable state of balance, where everything settles down.

Instead, just as, for example, international society is relaxing from one set of upheavals (such as the end of the Cold War), so a new set of challenges seem to start up (such as the rise of China and the comparative end of the US period of global domination).

Similarly in domestic matters, there is also a series of upheavals, such as the current changes wrought by computers, new media (like the current Facebook), and medical breakthroughs.

A society can never therefore be “relaxed and comfortable”. It has always to be on the guard against the implications of change.

The Challenge of Change

Littletown Shire Council – like the rest of Australian society – is wrestling with new challenges.

Part of the problem is that “change” itself changes. A person does not necessarily notice the changes with which they grow up: they take them for granted. Change is only noticeable when a person is an adult and they are having to cope with a new item or process.

For example, we now take cars for granted; they seem a standard item of Australian life. This has not always been the case. The first motorized vehicles appeared on Sydney streets in 1900[1]. They were imported and were playthings of the rich. Gradually cars became more available to the growing middle class.

Sydney City Council was therefore obliged to reassess the art of the making roads to cater for the heavier vehicles now travelling on them. Council’s learning process continued when it grappled with the faster movement of motorized transport, such as narrow streets, tight kerbs and corners and parked carts. Sydney’s narrow steep streets had to be extended, realigned, regraded and widened.

Cars created both unemployment and new forms of employment. For example, Council’s 19th century blockboys – staff who darted among traffic shovelling away horse manure – were no longer required. Meanwhile there was a need for people to refuel cars and maintain them. The first multi-level Council car park was opened in 1956.

The changes in employment may also be seen in another example. In the first Australian Census, just over a century ago, many Australians listed their occupations as “domestic” or “domestic servant”. Now very few, if any, will have listed that as their occupation in the Census.

Therefore the nature of economic activities changes over time. The economic term for this is “creative destruction”: as the winds of economic and technology drive along, so they both create new businesses and force the closure of old ones. Modern life is now one of continual change.

What Business are you in?

Sometimes even the largest and apparently smartest of corporations do not read the signs of change correctly. For example, the US railway industry was America’s largest in the 19th century. But by the 1920s the industry was in severe crisis.

Railways had as their main business the long distance carriage of passengers and freight. They had taken the business away from the vessels that operated on the rivers and canals – and then they failed to notice that they too were now under threat by new generations of technologies: cars, trucks and airplanes.

The railway financial crisis is a classic example of managers not answering the right question: “what business are we in?” They looked at all their physical assets – railway engines, freight cars and passenger cars, railway lines and stations – and thought they were in the railway business.

In fact, of course, they were in the transport business – and all the physical assets were simply a means to an end. They knew had to manage complex transportation systems, schedule deliveries, meet timetable requirements, and make passengers comfortable. But they were blinded by all their physical assets and so overlooked their intellectual skills.

They could have asked how – as people in the transport industry – they could apply their old skills to the new forms of transportation. But they failed to do so.

Value of Scenario Planning

How can we reduce the risk of being taken by surprise by change?

This scenario planning process is a way of trying to think about how Littletown Shire could change over the next two decades.

Change is inevitable – but it is not inevitable that we should be taken by surprise.

CHAPTER 2: SCENARIO PLANNING

INTRODUCTION

The scenario planning technique used in this “Littletown” Tomorrow document is derived by the scenario planning technique developed by Royal Dutch Shell and Global Business Network (GBN). The methodology has been adapted to incorporate community consultations.

This chapter explains the scenario planning technique. It begins with an overview of three ways of thinking about the future. It then explains the scenario planning technique in the context of “LittletownTomorrow”.

For people who wish to learn more about some of the specific applications of scenario planning, this chapter has an Annex containing some case studies of scenario planning.

THREE WAYS OF THINKING ABOUT THE FUTURE

The initial 2009 public consultation stage of the process covered three ways of thinking about the future: “prediction”, “preferred” and “possible”.

1. Prediction

“Prediction” means extrapolating current trends out into the future. This is the most common form of thinking about the future. Lines on graphs, for example, will often reveal a pattern. Here are three sets of examples.

First, economic predictions are perhaps the most widespread – and most criticized – branch of forecasting. Studies of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) which hit most of the Western world in 2008 have revealed the extent of the failure of extremely well-paid financiers to predict the future. Besides the allegations of inappropriate behaviour and downright greed, their actions also revealed a lack of awareness of history and context, a lack of thinking “outside the square” and an overwhelming optimism that ruled out any possibility of failure.

Second, by contrast, one of the greatest predictions made last century which will have a huge impact this century is “Moore’s Law”. Gordon Moore is a founder of Intel and on April 19 1965 he speculated on the increasing power of computers: every 18 months it will be possible to double the number of transistor circuits etched on a computer chip, and halve in price the cost each period.

Management writers Philip Evans and Thomas Wurster have warned organizations and companies that increasing computer power will transform business: This law has prevailed for the past 50 years. It is likely to prevail for the next 50 years. Moore’s Law implies a tenfold increase in memory and processing power every five years, hundredfold every ten years, thousandfold every fifteen. This is the most dramatic rate of sustained technical progress in history.[2]

Finally, CSIRO has a global foresight project in which it examines interlinked trends that will change the way people live and the science and technology projects that they demand. A 2010 discussion document[3] lists “five megatrends”:

- More from less. This relates to the world’s depleting natural resources and increasing demand for those resources through economic and population growth. Coming decades will see a focus on resource use efficiency.

- A personal touch. Growth of the services sector of western economies is being followed by a second wave of innovation aimed at tailoring and targeting services.

- Divergent demographics. The populations of OECD countries [the rich western countries such as Australia] are aging and experiencing lifestyle and diet related health problems. At the same time there are high fertility rates and problems of not enough food for millions in poor countries.

- On the move. People are changing jobs and careers more often, moving house more often, commuting further to work and travelling around the world more often.

- i World. Everything in the natural world will have a digital counterpart. Computing power and memory storage are improving rapidly. Many more devices are getting connected through the internet.

Some of these matters are encountered later on in the four Littletown scenarios.

2. Preferred

A “preferred” future is where a person or organization has a vision towards which they work and encourage others to share the dream. For example when President John Kennedy took office in January 1961 he knew there was a need for a bold vision to revive American spirits, which had been dampened by all the Soviet space progress, such as the 1957 Sputnik. On May 25 1961 Kennedy laid out his vision of putting a man on the Moon and returning him safely before the end of the decade. This was achieved in 1969. The Soviets, by contrast, never got to the Moon.

With a “preferred” future we move from what is currently being suggested by prevailing trends (“prediction”) to what we would like to see happen.

A good discussion starter is the management best-seller: Blue Ocean Strategy[4]. The authors claim that most strategy work is based on “red ocean” thinking – imagine the blood in the water from all the struggles – whereby firms are competing against each other. The authors offer a whole new approach: instead of trying to beat the competition, go elsewhere.

One of their case studies concerns the changing strategies for the automobile industry. Henry Ford’s 1908 Model T automobile was the first internationally well known US vehicle but this was not where the industry began. The US automobile industry dates back to 1893 when the Duryea brothers launched the first one-cylinder automobile in the US. The automobiles at that time were a luxurious novelty, unreliable and expensive. By 1908 there were about 500 US companies making automobiles.

Henry Ford decided not to compete in that “red ocean” and instead (in effect) used “blue ocean” thinking. His Model T was built for the middle class: it came in only one colour (black) and it was basic, reliable, hardy and durable. It was inexpensive: an automobile for the masses. US lifestyle, transportation and cities were all transformed.

3. Possible

Finally, “possible” futures are what could happen. They are not necessarily being currently suggested (via prediction) and they may not necessarily be what one would like to see happen (via preferred futures). The signs of possible change may be there – but one is simply not “seeing” them.

Detecting possible futures can be done via the management technique of scenario planning. Scenario planning is not so much about getting the future right – as to avoid getting it wrong. It encourages us to “think about the unthinkable”. Done properly, it reduces the risk of being taken by surprise.

The Shell Experience

A standard example of successful scenario planning concerns the work of Pierre Wack (1922-97), who was employed by the Royal Dutch Shell oil corporation. Oil (petrol) companies must make large capital investments in the face of extreme uncertainty. It is therefore a long-term industry in the sense that finding and extracting oil requires extensive investment. “Prediction” was a standard activity: predicting demand and then building the facilities to meet that demand.

The dominant worldview in oil companies in the 1950/60s was that oil was a “strategic commodity”. It was not an ordinary commodity, such as wool, coal and iron that varied in price. Because oil by then underpinned the Western way of life, the US and other Western Governments accorded its price and reliable supply a special status. Any attempt to disrupt the oil supply would be met by swift American action.

However, Pierre Wack “re-perceived” oil. What would happen if oil were in fact like any other commodity – and vulnerable to fluctuations in supply and price (like say, wheat and beef)?

Wack encouraged Shell to have contingency plans in place should there to be a disruption. That dramatic disruption came as a complete surprise to the West in October 1973. As the “Yom Kippur War” got underway, with the Arabs launching a surprise attack on Israel, so a second surprise took place on October 17: the Arab/ Iranian-dominated Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) implemented an oil embargo on selected Western countries and the price of oil quadrupled. Oil was never again to return to the pre-October 1973 price levels.

Wack had no way of predicting the 1973 Middle East conflict and consequent price hike. No one else had predicted it either. But he made sure that Shell was able to cope with any dramatic increase in oil price (and Shell was the only oil company in fact to do so). No other oil company had been willing to “think about the unthinkable” about any increase in the price of oil.

This was the classic scenario planning exercise: Wack had reduced Shell’s risk of being taken by surprise. From being one of the weaker oil companies of the seven big oil companies, Shell became the world’s second largest (after Exxon) and probably the most profitable. Shell was able to capitalize upon the 1973 crisis and went on to become of the world’s largest corporations. The reputation of Wack and scenario planning had been made.

ANNEX

EXAMPLES OF SCENARIO PLANNING

To conclude this chapter, since the technique of scenario planning may be new to some people, here are a few case studies that illustrate its value.

Most scenario planning is done as “commercial in confidence” and so is not revealed to the general public. It is, after all, a business technique and most businesses say little about how they operate except when they want to make announcements to boost their share price or public image (or defend them). Government departments are even more reluctant to share their inner workings.

Here are a few of the more well-known examples to show how the technique works in practice.

South Africa: The “High Road” and the “Low Road”

Pierre Wack, having retired from Shell, spent some time in the early 1980s in South Africa and was part of the team convened by Clem Sunter, then in the country’s largest corporation Anglo-American, working on scenarios of South Africa’s future. South Africa was under the apartheid regime, which seemed destined to stay in place indefinitely. However the corporation did not think that apartheid could last forever and so decided to encourage public debate on possible futures for South Africa.

Sunter toured the country speaking on two scenarios: the “high road” and the “low road”. The “high road” was a story of the release of Nelson Mandela (then the world’s longer-serving political prisoner), the creation of multi-racial electorate and Mandela’s election as the first black President. His white audiences were outraged.

Sunter would then explain the “low road” scenario as a story of the country falling into increasing sporadic violence, continued international isolation, a white exodus to safer countries and a generally grim future. This encouraged his white audiences to ask for more information on the “high road” scenario.

In March 1989 Frederik de Klerk was elected President. Max Hastings was the then the Editor of conservative The Daily Telegraph (London) and recalled the mood of those years in his memoirs. Few observers, including his own journalist in South Africa, anticipated just what would follow because no one expected de Klerk to be any different from his predecessors.

But on February 2 1990 de Klerk suddenly lifted the 33-year ban on the African National Congress and invited Mandela to join him in negotiations towards a constitution which would grant the vote to the country’s African majority. This drama was occurring around the time of the ending of the Cold War. Hastings concluded his survey of that 1990-1 period:

Which of our generation would have dared to predict, even twenty years ago, that we should see within own lifetimes, an end to the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Empire, and a relatively peaceful transition to black majority in South Africa? Much of the business of newspapers is to purvey tales of disappointment, failure, tragedy. How intoxicating it was, that for a season, we found ourselves bearers of historic and happy tidings on two of the greatest issues that faced the world in the second half of the twentieth century.[5]

I have my own footnote to this story. In 2001 I was a guest of Annette Liu, then the Vice President of Taiwan (the most senior woman elected in 5,000 years of Chinese history) at her seminar of Nobel Peace Prize Winners in Taipei. Frederik de Klerk was one of the Nobel participants. He knew nothing of my professional interest in scenario planning. But quite spontaneously, while explaining how he was able to manage the transfer of power to black majority rule, he paid tribute specifically to Clem Sunter who had given the scenario talks in the 1980s and had created the political opportunity for de Klerk to make his historic reforms. Sunter had helped white South Africans to “to think about the unthinkable”.

Smarter Than Governments

Shell has a legendary reputation for making the most of knowledge, not least in using it to assist the company’s future economic growth – but governments have been slow to acknowledge Shell’s skill. Here are British and American examples.

Australian authors Peter Thomson and Robert Macklin have claimed that as early as 1953, Shell was warning that the Anglo-French-owned Suez Canal could be nationalized by Egypt. The warnings were ignored. Shell staff were told:

…that if Egypt seized the Canal illegally, the company would expect France and Britain to reclaim it by military action. In 1956 President Gamal Abdul Nasser nationalized the Canal, as Shell had foreseen, precipitating the Suez Crisis in which Britain, France and Israel failed in their efforts to seize it through military intervention, forcing British prime minister Anthony Eden to tender his resignation.[6]

Peter Schwartz took over from Pierre Wack at Shell. Two years later, in 1983, he proposed to the Shell senior executive team that his unit look at the future of the Soviet Union. Shell bosses were sceptical. The Cold War was in deep freeze, with President Reagan’s reference to the “Evil Empire”, Mrs Thatcher’s own hatred for the regime (Shell is partly headquartered in London), and Soviet leader Yuri Andropov’s own mutual antipathy towards the West. Additionally the USSR was not a supplier of oil to the West. But, Schwartz argued, it had some of the world’s largest oil and gas reserves and so it ought to be on the Shell research agenda. He eventually won approval for the research.

Two scenarios were devised: “Incrementalism” and the “Greening of Russia”. The latter contained the possibility that if the largely unknown (to the West) politician Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, he might well push ahead with economic and social reforms. It would not be so much due to Gorbachev personally but that his arrival in power would be a symptom of the underlying pressures for reform for which he would be the spokesperson. Schwartz’s account continues:

Shell has a habit of presenting its global scenarios to government agencies, in part to glean their reactions. Every Soviet expert but one told us we were crazy. The exception was Heinrich Vogel of Germany. The CIA said, “You really don’t know what you talking about. You just don’t have the facts.”

In retrospect, people have credited our research, but the CIA certainly had access to the all the data we did. Our insight came solely from asking the right questions… If we had to pick only one [scenario], we might have been just as wrong as the CIA.

We ourselves did not know for certain that things were moving towards our “Greening” scenario until Gorbachev was elected. But having more than one scenario allowed us to anticipate his arrival and understand its significance when he ascended to the leadership.[7]

The CIA was hampered, at least in its public pronouncements, by the “official vision” to which it had to direct its attention. In other words, the word from the White House was that the USSR was the “Evil Empire” (in Reagan’s 1983 phrase) and that the US and USSR were on an arms race to the finish. The “official vision” blinded the CIA to looking for signs of change.

Earlier in his book, Schwartz pays tribute to his predecessor Pierre Wack and the rest of Wack’s team. But it is necessary not only to praise Wack and his team, but (according to Schwartz) we should also to acknowledge the role of the Shell bosses: “…it [was] thoughtful and farsighted Shell executives who invited him into that role in the first place, provided him with the resources he needed and paid him the compliment of listening to him and taking him seriously”[8].

By implication this helps explain the failure of the CIA to identify the signs of the peaceful end of the Cold War: it had had no official encouragement to look for the signs of such change. The Reagan White House was so focussed on the “Evil Empire” it was unwilling to “think about the unthinkable”.[9] Much the same could be said about some other foreign policy failings[10].

Australia’s Economic Futures

Dr Graham Galer, a UK national, was also a Shell planner. He spent 36 years in Shell and retired in 1993. While based at Shell Australia in the late 1970s, Galer assisted in a variety of ways with a scenario planning project on Australia’s economic future. The resulting book[11] was not a formal Shell project – simply that Shell wanted to assist the debate over Australia’s possible economic futures.

The book was completed in December 1979, while the Fraser Liberal-National Government was still very much in power. It was still a time of government intervention in the economy, high tariff barriers, extensive government regulation of the economy with close co-operation of the unions (sometimes not quite so friendly – but they were always a power to be reckoned with). This was broadly the economic philosophy that had underpinned the country since federation in 1901. Political parties may have differed over the details but broadly there was support for a managed economy.

The authors set out two scenarios of Australia’s economy to the year 2000. One was “The Mercantilist Trend”, which was based on a continuation broadly of the then present situation, and its advantages and disadvantages.

The other was “The Libertarian Alternative” which, to use more modern jargon, would see a future of de-regulation, reduced tariffs, reduced involvement of the government in the economy, and selling off of government assets (“privatization”), leaner, more efficient companies, and with the end of the “jobs for life” mentality.

In 1979 such a scenario was no doubt thought “unthinkable” by contemporary politicians. But in fact, from 1983 onwards, with the election of the Hawke Labor Government that is how the economy has evolved and has been continued by all the subsequent governments.

Had more people read the book in the early 1980s they would not have been taken by surprise by the economic revolution that Australia has lived through since that period.

Australia’s Aging Futures[12]

In 2000 UnitingCare NSW was one of the few not-for-profit groups operating viably in aged care. That was the result of a concerted focus on efficiency in management and profitability over the previous decade. However, the surpluses generated were not great in percentage terms and hence very sensitive to changes in government funding policies. The withdrawal of capital funding from government over the previous decade, and additional structural changes to the funding of aged care with the introduction of the Aged Care Act 1997, made it difficult to regenerate the capital requirements for high care facilities in particular.

I was involved in a scenario planning project which was seen as one tool to help to make sense of changes and to help shape the organization’s future. There was a large number of “unknowns” around the future of aged care. For instance, what service models might exist in the future? What will older people want in terms of the way they receive the care they need in older age? How will aged care be financed? There was also a need to consider how the delivery of services and the degree to which physical facilities either supported or potentially hindered longer-term service development. Traditionally, delivering services from a base that had a large investment in buildings could make it difficult to move in other service directions and to develop alternative ways of delivering care services in the homes of clients.

The process commenced in November 2000, seeking to answer the questions: “What are the alternative, plausible scenarios for the future of aged care in Australia, and what are the most robust strategies for the Ageing & Disability Service to pursue to respond to those strategies?”

The report (which was our personal opinions and did not necessarily reflect the official views of the Uniting Church) contained four scenarios. In following the STEEP questioning format while interviewing the experts, we found that the two main drivers of change in this context would be Economics and Technological Change. We then used the two axes to create the four quadrants.

We had a problem in trying to imagine an Australian aged care “future” in which there would be high economic growth and low technological change. We thought that in a demographically small and reasonably homogeneous country like Australia, high economic change would always affect technological change. In the US, by contrast, some communities can live in technologically limited locations isolated from the rapid pace of economic change (such as the Amish/ “Pennsylvania Dutch”) but we could not see that possibility in Australia.

Our first scenario, then, we called “Business as Usual” and placed it in the centre of the two axes. This was where our clients (the 52 aged care boards then sat): they had survived the 1997 Aged Care Act (the most extensive change to aged care legislation in Australian history) and assumed they could survive the forthcoming accreditation/ registration reviews foreshadowed under the new legislation. Even so, we did foreshadow some reasons for avoiding complacency, such as the shortage of medical personnel. We also politely raised the issue of governance: namely that the 52 boards of often well-meaning but poorly trained individuals were now running multi-million dollar businesses but may not have the full range of skills to do so.

The second scenario we called “Brave New World” and it was based on high technological change/ high economic change. Under this scenario we imagined a future of great medical and economic progress. In the Brave New World novel there are no old people: people live very active lives and as they start to age so they were dispensed with via hallucinating drugs (as the author Aldous Huxley himself went in his final days). The implication here for the provision of aged care, is that there would be little demand for “low care” facilities because people would want to stay for as long as possible in their own homes but there would be a high demand for “high care” places for the final stage of life (the “compression of morbidity”).

The third scenario was “Blade Runner” and it was based on high technological change and low (or uneven) economic growth. As in the movie Blade Runner we imagined a world of greater disparity between rich and poor, with the rich living in “gated suburbs” and the poor surviving in ghettos. The latter would present challenges for the delivery of community care: how could the safety of community care workers be guaranteed in rundown violent locations?

The fourth scenario was “Out of the Rat Race” and was based on low or uneven economic change and low technological change. People would have grown weary while in the workforce of being “down-sized”, de-layerized”, privatized, and so were opting for a quieter life after leaving the workforce. While the report was being publicized some people said the scenario encouraged them to think of the then popular television programme Sea Change. Again, under this scenario, older people would be opting to stay at home for as long possible and not require the billions of dollars’ worth of UnitingCare aged care bricks and mortar – few of which anyway were built anywhere near “sea change” coastal resorts or rural “beauty spots” (such as vineyards).

The report was launched in October 2001. It contributed to the subsequent major restructuring of the aging service, with the enforced amalgamation of local aged care boards into regional ones (and retrenchment of some local executive staff) and the up-skilling of the boards, with a much larger number of central staff at Head Office to cope with the increasing government regulator requirements. Aged care has become (as the government expected with the 1997 legislation) a much more professional undertaking.

Compiling any scenario planning document is, effectively, the “upstream” first part. The “downstream” second part is talking up the document, obtaining ownership of it, embedding it within an organizational culture, encouraging staff/ volunteers to be on the look-out for the indications that one particular scenario is coming into play. I have continued to do this in a personal capacity on the corporate speaking circuit.

To conclude, of the four aging scenarios which one, a decade on, seems to be coming into play? It seems to be “Brave New World”. As an aged care trade magazine recently explained:

Low care is suffering a slow and significant death. As a proportion of aged care services, low-level residential care is in distinct and continued decline. Of the existing residential aged care population, 70 per cent of residents are classified as high care and in recent [government aged care] approval rounds, new high care beds are being allocated at nearly twice the rate of low care beds.

The death of low care is at the hands of both consumer preferences for community care services as well government policy that shifts necessary funding dollars away from low care provision.[13]

CHAPTER 3: INTRODUCTION TO THE FOUR SCENARIOS

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this chapter is to make some introductory observations about the following four scenarios and the process of their creation.

THE TWO DRIVERS

Whenever two or more scenario planners are gathered together and start discussing their respective projects, a key question is: “what drivers have you selected?” There are five drivers: Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental and Political (STEEP). In interviews with experts, a standard question is usually around what factor(s) is/ are driving the change. As the interviews progress, so it should become clear that a particular two are the most important and are the most often recurring in the responses.

Each driver then becomes an axis, with “high” at one end and “low” at the other.

For Littletown, the two main drivers of change were Economics and Environment.

They are then used to form an upright “cross”: +. The horizontal (Economics) and vertical (Environment) axes then provide four quadrants:

. top left hand quadrant: high Environment/ low Economics: “Back to Nature”

. top right hand quadrant: high Environment/ high Economics: “Green Littletown”

. bottom left hand quadrant: low Environment/ low Economics: “Ghost Town”

. bottom right hand quadrant: low Environment/ high Economics: “Brown Littletown”

The scenarios are set out in the following order:

- chapter 4: “Back to Nature”

- chapter 5: “Green Littletown”

- chapter 6: “Ghost Town”

- chapter 7: “Brown Littletown”

PREVIEW OF THE FOUR SCENARIOS

- “Back to Nature” suggests a Littletown with little economic activity because most people have moved out of the shire; the environment is in good shape but people aren’t much interested in staying; city life is far more profitable and interesting.

- “Green Littletown” suggests a shire that is making the most of sustainable development and the new “green economy”, and a growing Chinese market for food, and so it has a thriving economy

- “Ghost Town” suggests a Littletown with severe economic and environment problems existing within an Australia where national and state governments are far more worried about urban voters and priorities than the handful of people still living on the land.

- “Brown Littletown” suggests a shire benefiting from the knowledge economy, a thriving service sector and an expanded nearby regional city; the population is large and expanding.

FORMAT OF EACH SCENARIO

Each chapter has four components:

- summary of the scenario

- the drivers for that chapter

- indicators of when that the scenario could be coming into play

COMMON CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FOUR SCENARIOS

Each scenario has to be plausible. It is not a matter of whether one may like or dislike it. The test of a scenario’s success in the first instance is whether a reader can say to themselves “Yes: I could imagine such a thing happening”.

The scenarios are not “predictions”. They are not suggesting that this is inevitably Littletown’s fate. Instead, each scenario is designed to assist people to speculate on what could be Littletown’s fate, to think about the unthinkable and to generate new ideas on what could be done.

Finally, it is worth noting that one piece of information may appear in more than one scenario. It is in the nature of scenario planning that the same event/ process/ organization may be viewed in different ways in different contexts.

CHAPTER 4: “BACK TO NATURE”

INTRODUCTION

This scenario sees a Littletown with a healthy environment but few people wanting to live here and so little economic activity. As some people leave the area, so others follow suit because there is no economic reason to stay on. Gradually the area continues its trend towards depopulation.

The rise of “new right economic rationalism” in the early 1980s meant an end to government “nation-building” and strategic involvement in the economy, with instead a greater reliance on the “market” and just letting economic forces take their course. Littletown’s economic decline is just an unfortunate facet of Australia’s overall economic transformation and rural depopulation. Littletown’s demographic decline is therefore a part of the overall pattern of rural decline in Australia. This scenario continues to see a continued migration out of the shire.

THE DRIVERS

High Environmental Quality

While some other parts of Australia are having environmental problems, Littletown is comparatively safe.

The area is attractive to some people who wish to live in a quiet, rural lifestyle. Most of the money from agricultural work is made by people who live outside the area (the large pastoral corporations) but some people work in small-scale agricultural activities because they find the easy-going lifestyle appealing. They are reconciled to having less income and fewer economic activities, and they know their children will leave the area at the first chance.

Low Level of Economic Activity

The decline in economic activity is due to eight factors. First, much more money can be made elsewhere. Young ambitious people prefer to work in the big cities or mining areas. Littletown is seen as “boring”, with only a limited range of attractions for ambitious young people. Besides, life on the land is seen by them as too hard and too economically precarious. They prefer the buzz of inner city life.

The loss of young people, particularly those in their 20s and 30s, has robbed the community of potential leaders and innovators, and consequently has undermined community vitality and even hindered the emergence of creative regeneration strategies.

On the other hand, the reduced number of young people means a reduced level of crime because most crimes are committed by young men. Littletown residents, though physically isolated, feel fairly secure because of the absence of young people with their drunkenness, noise, violence and strange hours of activity.

Second, in particular ambitious young Littletown women now have their own careers to think about. For the first time in Australia’s history, they are better educated than young men. Tertiary education has siphoned young women out of rural Australia and into the tertiary education facilities in the cities, where they stay on to seek employment in a wider world of opportunities in Australia and overseas. Young women are less willing to stay in rural areas to do local jobs to supplement farm income. Education has opened up a whole new world of opportunities to them.

Littletown people moving to the city now have a different orientation. Rural life encourages people to build community on the basis of where they live and so they are reliant on the co-operation of neighbours. But city life provides a different orientation. City culture encourages the more mobile formation of temporary communities of interest based on work, entertainment, sporting activities and hobbies. Young people also like the fact that city life is more anonymous and individualized; what they do in their private lives won’t get reported back to their relatives.

Besides, if people want more friends they can do so on modern information technology such as the old Facebook. Technology has reconfigured notions of distance and social connections.

It has also reconfigured work and the hours of work. People go on and off shifts at different times and so want to relax at different times. Littletown does not, for example, have a café or hotel open at 3am for people coming off work and not yet ready to head home for sleep. Cities never sleep.

Third, Littletown’s average age is increasing faster than the national average. It is seen as a locality for the genteel elderly, and others who like the easy-going lifestyle and are willing to have lower level of income than they can make in cities. The increasing percentage of older people tends to reduce the overall level of economy activity because they have less money to spend and are more cautious about where and how they spend it.

Fourth, Littletown has suffered from the increasing “bush-city” divide. Only one or two generations previously, almost everyone in a city had relatives working on the land. With the de-population of rural areas like Littletown, many city people now have little direct contact with rural areas, except for vacation outings. They may enjoy the holidays in Littletown but would not want to live there permanently as it is too quiet and lacking the level of services they are used to in the city. For example, as Australia’s average age has increased, so there is a greater anxiety about rapid access to good hospitals; the bush is perceived as lacking in such facilities.

Over 90 per cent of Australians now live in city and suburban areas. The bush-city divide is not simply one of geography. City people like, for example, their steak and eggs but have little direct knowledge of how the food came to be in the city shops and restaurants – and they don’t care. They want out-of-season fruits and vegetables – but don’t care if they have come from, for example, Brazil. They are just worried about their own interests – and leave the farmers and others to worry about their own.

A by-product of the drift to the city is that few people now worry about happens to the rural sector. In political terms, the focus is on marginal constituencies and they are more likely found in urban areas (such as western Sydney) rather than the declining population base (and so declining political representation) of the rural sector. There are, in short, few people in the Canberra and Sydney corridors of power willing to advocate on Littletown’s behalf. There is also a declining number of politicians with direct experience of living on the land.

Fifth, as with the rest of rural Australia, Littletown is caught in a downward spiral that is underway – with a reduction in one service area leading to reductions in other services. For example, the reduction of young people requiring education means a reduction in schools and so the exit of school teachers means that, for example, fewer financial services and retail services are required.

Sixth, this decline in provision of services is accelerated by the growth of online services. With the improvements in computer technology, people can shop and bank online and so there is reduced need for local staffed outlets.

Seventh, many agricultural activities have been aggregated: “you get big or you get out”. Marginal farmers have been encouraged by the Australian Government to leave the land. Once they sell up, they tend to move out; there is little to now keep them in Littletown.

National and state governments have agreed that measures such as drought relief provide perverse incentives: they encourage marginal producers to stay on the land when they really should get off it. Such measures provide a margin of comfort when family producers should really take greater notice of the price signals and just quit farming.

Many local owners have been replaced by large pastoral corporations which employ farm managers. The managers tend to stay in Littletown for only a few years and move on. Their loyalty is to the company and the development of profitable activities. They have little interest in Littletown as such.

With the decline in the local population, there is a reduced state government incentive to provide long-lived assets, such as roads. The roads are required simply to transport what remains of the economic output; there are fewer people to worry about.

Finally, the decline in population has led to the decline of local non-governmental organizations, such as churches, Rotary, and Meals on Wheels. This decline has eroded the social fabric of Littletown, with fewer opportunities for social interaction and engagement. The “rural way of life” is fading away.

INDICATORS TO WATCH FOR

- young people leave the shire to seek education and work opportunities in the cities and overseas

- average age of Littletown residents is higher than the national average

- Australian “rural heritage” is mainly for overseas marketing purposes; it is cheaper for urban Australians to import food

- declining political impact of the rural sector on Australian politics

- reduced government assistance for rural economic activities

- government encouragement for rural residents to move into the cities

- aggregation of family farms into larger corporation-owned properties

- online shopping replaces much of the local shopping

- decline of community organizations

CHAPTER 5: “GREEN LITTLETOWN”

INTRODUCTION

This scenario sees Littletown benefiting from an Australian Rural Renaissance. Littletown’s population has grown but it still sustainable and the environment remains in good condition. The economy is flourishing.

The extent and form of the renaissance varies from one part of rural Australia to another but there are some common factors. First, there has been a rejection of the dominant economic paradigm of “economic rationalism” from the 1980s, with its emphasis on narrowly focussed self-interested “get rich quick” thinking, and now there is a dominant paradigm based on the longer term and broader focus of “sustainable development”. The emphasis on economics has been replaced by a focus on ecology. There is also a wider acceptance that the global environment really may face some severe problems and so new ways of thinking are required.

Second, there has been a renewed emphasis on food self-sufficiency. Australia has started to import more food than it exported. In the following years there was a national debate over should be done to again make sure that Australia is a food exporter and has greater self-sufficiency in food production.

Third, Australia is geographically well placed to make the most of the global new era. It is in the safest corner of the globe, away from the “failed continent” of Africa, and near to the growing markets in Asia.

THE DRIVERS

Sustainable Development

“Sustainable development” is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

It is not purely an economic matter because it assumes that organizational survival (whatever form the “organization” takes) includes community relationships, supplier and customer relationships, and employee engagement (and ratepayer engagement). It ties together environment, economy and community; it doesn’t optimize one over another; it doesn’t trade off one against another.

This is now Australia’s main economic philosophy. It is unfashionable and politically unacceptable simply to focus discussions on “what’s in it for me?” and “what is the bottom line?” That economic philosophy triggered the financial crises that ran on and off throughout the early 21st century and continues to haunt the globe in 2030.

A sign of the new reasoning has been the dropping of GNP (gross national product) as the standard economic benchmark. It was too focussed on financial flows and not on better indications of economic activity[14]. It measured only financial flows and not other forms of activity[15]. It assumed that any increase in GNP was always beneficial; when in fact not all GNP increases benefited society[16].

The new official accounting system is based on a complicated formula derived from economic, environmental, and social indicators. The new accounting system changed perceptions. Instead of daily broadcasts of the state of the GNP there were daily reports on the state of the well-being index. Once the new accounting system became the national and international standard, it was clear that the shire of Littletown was a valuable area: not only in agricultural terms but also due its geographical location, stable population, low crime rate and good social cohesion.

Food, Fibre and Fuel Security

In 2009 the number of undernourished people on the planet topped 1 billion for the first time. Since that time that has been a growing global recognition that the world will run out of food before it is overcome by rising sea levels. The global factors included rising population numbers, the effects of warming on agriculture on the hotter regions, and the habit of people eating more protein as countries become richer. In China, for example, meat consumption has roughly doubled ever decade since 1985.

Therefore Australia’s national emphasis on food and fibre security arose partly out of a broader definition of “security”. The traditional definition had been with a military focus. The new definition has a much broader focus and includes economic, social and environmental factors.

The national strategy on “food, fibre and fuel security” recognized that the three components were inter-related: for example, fuel transports food and so more expensive fuel will flow on into the price of food, while food can become a form of vehicle fuel (eg ethanol) and so could adversely affect some food prices.

The Australian Government therefore decided that more resources should go into reinforcing the agricultural sector.

All local governments are now required, as part of their strategic planning, to show how they are responding to the national strategy on food, fibre and fuel security.

Australia as China’s “Breadbasket”

China is now the world’s main economic locomotive. The Great Wall of China has become the Great Mall. There was a Chinese recognition in the late 1970s that socialism has failed and that a greater reliance should be placed on the market system. This economic revolution has resulted in the biggest rise in income for the biggest number of people in world history

China is recovering its sense of global importance. 1,200 years ago the Tang dynasty stretched from the South China Sea to the borders of Persia (Iran). China pioneered the development of, for example, papermaking, cast iron, gunpowder, and paper money. But as China fell into decay, so it failed to make the most of these inventions; all of these had to be re-invented again by the Europeans in the last half millennium or so. In more recent centuries China went even more into decline and fell prey to warlords, civil wars and some European colonization. But now China is getting back on its feet and it expects to the global superpower around 2050.

However China’s booming economy is coming at a great environmental cost. For example, urban expansion, road construction and the creation of new factory sites all come at the cost of existing agricultural land use. Water tables are falling, desert areas are increasing, and some of China’s fragile topsoil now even gets carried in the wind across the north Pacific to the western US and Canada. There is industrial pollution in the atmosphere and rivers (16 of the world’s 20 most polluted cities are in China). Even the Yangtze, which supplies water to a twelfth of the world’s population, is showing signs of stress because of the creation of super-cities like Chongqing (with 30 million people).

Australia is favoured supplier of food to the rising Chinese middle class. It is seen as a clean, reliable and stable supplier. Littletown has benefited from this.

Greater Environmental Protection

The increase in natural disasters in recent years has forced some changes to the political culture.

All national and governments have become more aware of the need to protect the environment. There is now extensive environmental legislation.

Second, there is now greater public and media support for “green” policies. All the old environmental battles of the late 20th century/ early 21st century seem a long way away. Newer generations of Australians cannot imagine what all the fuss was about. Ecology is a compulsory subject in all Australian schools.

A third indication of the new era is that old “green” political issues have become so mainstream that the traditional green political parties have largely disappeared as separate entities, with their more ambitious members going into the other more mainstream parties to further their own political careers. There was no longer much political mileage in being a “party of protest” when the issues had become conventional thinking.

The remnants of the green parties became reinvented as the parties of small business people who had felt left out of the debate in which unions and big corporations dominated. Some of the remaining Littletown family farm owners are members of the new green political alignment.

INDICATORS

- “sustainable development” is the new dominant paradigm

- rejection of the “economic rationalism” paradigm

- “ecology” is taught in all Australian schools

- new government ways of measuring “progress”

- a national strategy for food, fibre and fuel security

- Australia is a “breadbasket” of China; close trade links between Littletown and China

- people moving into Littletown for the business opportunities

CHAPTER 6: “GHOST TOWN”

INTRODUCTION

This scenario sees Littletown as largely deserted. The global, national and local environment is in a bad state. Meanwhile, there is virtually no economic activity in Littletown. There is little national or state political attention to the dire situation in rural locations like Littletown; environmental and economic problems in the cities take priority over the comparatively small number of people still left on the land.

Indeed the politicians have advised Littletown residents to quit the area and move into cities where they can receive assistance and perhaps new employment opportunities.

Therefore most Littletown residents have decided to leave the area and head for the city.

THE DRIVERS

The environmental crisis has come from four factors. Their overall impact is the perception that the subject is too complicated (even for people who are well-meaning) and so people prefer to opt of that challenge and focus on less challenging matters, such as entertainment, celebrity gossip and sport.

The Global Environmental Crisis

At the international level little progress has been made in governments to co-operate to protect the environment. China and India – now both the largest emitters of carbon pollution for some years – have been unwilling to reduce their immediate economic priorities in order to protect the environment. Similarly Latin American and a handful of developing African countries are now proceeding at various speeds with their own economic development and accord the environment low priority. All these countries say they will only start to heed western warnings about the need to protect the environment when their own citizens enjoy the standard of living that westerners have enjoyed in the past century or so.

Australia has been in a dilemma. On the one hand it has urged developing countries to do more to protect the environment (and so curb their ambitious growth targets). On the other hand, Australia remains an important international exporter of raw materials and so welcomes those ambitious growth targets as further economic opportunities for Australian exporters. For example, Australia still has enough coal to last for four centuries. It is safe to use, easy to mine, safe to transport, and safe to store. Australia remains the largest world’s coal exporter.

Australia – while being a per capita very high emitter of carbon – is in an aggregate sense a minor player (at about one per cent of total emissions) because of Australia’s overall small population. Any unilateral initiative by Australia is negated by China or India within a few months.

Meanwhile, the United States is providing little environmental leadership. Americans – at both the political and personal levels – have been unwilling to drastically reduce their reliance on automobiles, change the building codes to create more energy-efficient buildings, or provide tax payer money or private investor money for new technologies.

“Sustainable Development” – Unsustainable

Western governments continue to speak about “sustainable development” but it is largely a meaningless phrase. There is little agreement on what it actually means – indeed some people claim that its continued existence is unsustainable.

There is a “green gap”: a gap between what people should do and what they actually do on the environment. Public concern about the environment has not been converted into public policy. Many Australians acknowledge to opinion pollsters that climate change is a problem but they are not willing to take drastic action to do something about it. Sure, they may use less water when brushing their teeth but they are unwilling to forego the latest domestic appliances. They just hope that the main environmental crisis can be postponed for the coming next few years – and so leave the problem to their descendants to sort out. In the meantime most Australians are more worried about the health of their favourite sports player rather than the health of the planet.

“Carbon Cowboys”

“Carbon cowboys” are the new category of businesspeople who exploit public concern about carbon pollution by offering schemes to reduce carbon pollution – but which really don’t necessarily do much good (except for their own income). They are old-style profiteers with new environmental issues to exploit.

For example, there have been many schemes offering to plant trees to “offset” the emissions associated with (say) an aeroplane flight. The problem is that even if the trees do get planted (and there is no guarantee they will be), the flight is an immediate emission, while the tree will take many years to recapture the carbon emitted by the flight.

More generally there is a feeling that planting trees isn’t enough anyway. Inevitably new forests eventually become saturated with carbon and so begin returning most of it back to the atmosphere. Whether the trees are lost to fire, or die of old age or from insect damage, the bulk of their carbon sooner or later turns back into carbon dioxide and is re-released.

Finally, carbon trading schemes have also suffered the classic tensions of all capitalist markets: volatility, overproduction and manipulation. A lot of investors have had their fingers burned.

Collision of Environmental Values

The “carbon cowboys” are also the tip of colliding environmental values iceberg. They are exploiting the public’s concern about climate change and, even if the schemes are honestly implemented, they are simply offering a cheap way of solving a person’s environmental conscience.

The most destructive aspect of carbon trading is that it allows people to believe they can carry on polluting – and so avoid making big decisions to change their way of life.

The fact is even the most well-meaning of people with a concern about the environment are confused about how they should act. For example people have tried to make greater use of bicycles in the cities but this has only added to increased hospital emergency department admissions. People have also tried to forego some use of cars but all of the Australian cities have poor public transport systems. There is little opportunity to repeat the grand transportation schemes of the 19th century. For example, with so much land built over, it is now almost impossible to acquire enough land to lay down new railway lines. Environmental lawyers and environmental activists have blocked proposed large development schemes: “green litigation and environmental red”. There is no political or media appetite for grand nation-building schemes.

Economic Decline

“Peak Oil”

The controversy over “peak oil” (also called the “Hubbert peak” refers to oil (petrol) production reaching a peak, where about half of the supply of the find is used, after which production become more difficult and more expensive to get out the other half.

The controversy was triggered in 1956 by Dr M King Hubbert (1903-89) who was a pioneer in the application of physics to geological processes. He was an American geologist working for Shell. He predicted that US oil production would peak around 1970 (he was proved right) and that global output would peak in 1995. He got that date wrong – but only by a few years.

There is a difference between actually running out of oil – and no longer finding oil at the same rate it is being drilled. It is like getting apples off a tree: there may be apples right at the top but would you want to make the all effort to get there? Similarly, there will still be oil around in a century’s time – but at deeper and more dangerous depths.

Oil still meets 40 per cent of the world’s energy needs and nearly 90 per cent of transportation needs. Additionally, given the significance of oil for modern economies generally (plastics etc), the oil crisis has flowed through to the rest of the economy and so there is more to the “oil crisis” than just the price of petrol for cars.

There is still oil being used in Australia but it is now at a much higher cost and people are more cautious about how they use it. Isolated rural areas like Littletown, with limited public transport access, are too expensive to visit on a regular basis. Besides there is little to do even if one were to visit.

Rural Areas are Seen as Unsafe

The fear of crime has led to increasingly atomised lifestyles for those that can afford them, with wealthier people retreating into their homes, cars and offices – which ironically further disconnects them from the wider community and increases their suspicion of others.

Therefore another problem for rural communities like Littletown is the growing perception that such isolated rural areas are unsafe. With the continuing movement of people into Australian cities and the improvements of crime monitoring technology, city life is now seen as the safest it has ever been. But it is too expensive to use the crime monitoring technology in isolated rural areas such as Littletown with a small population.

Littletown as Uninsurable

Littletown is becoming uninsurable. Besides the risk of increased crime, insurance companies are worried about climate–related damage. The problems are not simply the dramatic events of extensive floods and mega-fires, but the increased wear and tear as a result of the climate becoming increasingly harsher.

These debilitating weather events include: an increase in extreme daily rainfall, substantially more severe wind and lightning (which could for example damage transmission lines and structures), and heightened storm activity that could result in flood damage to roads, rail networks, bridges, and airports.

National and state governments are encouraging rural residents to evacuate their isolated locations and move into safety of the cities.

INDICATORS

- increased global, national and local environmental problems

- lack of international progress in protecting the global environment

- discrediting of the economic incentives in environmental protection schemes by “carbon cowboys”

- increased oil costs and increasing speculation that the “world is running out of oil”

- migration of people out of Littletown Shire

- increased insurance costs for remaining Littletown residents

- increased rural crime

CHAPTER 7: “BROWN LITTLETOWN”

INTRODUCTION

This scenario sees Littletown as a thriving increasingly urbanized shire with high economic activity, with citizens using new information technology and other new business opportunities. Littletown is making the most of the “knowledge economy” and the opportunity to expand services.

There are continuing tensions with citizens who would prefer a smaller population and a greater continuation of the agricultural way of life. Other citizens by contrast want to make the most of new ways of earning money, not least as the local regional city itself is also expanding and so Littletown can assist with that city’s economic development.THE DRIVERS

Information Technology

Moore’s Law on the increasing power of computers has continued to hold up and Australia is doing well in the new era.

Work is something you do – rather than a place you go to. Improvements in information technology have meant that much more work can be done away from the city. People now work far more from homes – and so they have acquired larger homes to run their own home offices. One of the reasons for Littletown’s popularity has been the available space for additional and larger homes. The “Littletown country mansion” is a recognized national home building style modelled the grand 19th rural country homes.

Each home is now far more energy self–sufficient thanks to solar energy.

Many new employment opportunities have been opened up to cater for information technology.

Knowledge Economy

Australia has just been through the biggest economic transformation since the 1980s.

Australia had long been a “First World country” with a “Third World” economy. In other words, it enjoyed a very high standard of living but relied on the more traditional economics of extracting wealth (food, minerals and energy) from the land (much like a developing country in Africa).

The new knowledge economy (pioneered by the United States and Singapore) meant that fewer people worked on the land (or in factories) with their muscles, and instead they had to acquire the ability to transform the mass of information now available into innovation that can be used to make many different products or the same products in a smarter way. They work more flexible hours and many live in many different places. They don’t need to work in a city Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 – indeed they don’t want to.

The workers are “symbolic analysts”. They don’t use their hands to grow food or work a lathe in a factory. They handle symbols all day: numbers, words, notes of music, diagrams etc.

Their work is more fluid than the traditional world of jobs. “Jobs” were invented in the Industrial Revolution (which began in the UK around 1750). People went off to work, sold their labour for a set amount of money, and returned home at the end of the working day as a haven from work.

Now there are no set “edges” to a person’s work. Information technology means that they work in an unstructured way wherever they happen to be. Good ideas can occur on the golf course or in the shower.

Rediscovery of the Importance of Regional and Rural Australia

Australian and state governments have recognized that the capital cities cannot continue to grow and so they have made a greater effort to decentralize away from the capital cities.

Australia’s population is on schedule to reach at least 35 million by 2050. This has been primarily due to the increased skilled migrants from overseas to help maintain Australia’s economic expansion. Also Australians are continuing to live longer and so a few of the people who have lived longest in the world are residing in Australia.

The geographical expansion of cities had become a problem. As the cities expanded so prime agricultural land used for market gardens was being lost.

More significantly cheap housing built on the urban fringes, remote from public transport, is actually not “cheap” at all when the cost of driving to work, school and colleges, shops, recreation and health services were taken into account. Total motor vehicle expenses were becoming too much of a political hotspot. Green politicians had also insisted on redefining economic accounting so that “total motor vehicle expenses” also included health trauma costs from road accidents, the healthcare costs of the stress on the human body involved in sitting in traffic jams, and pollution being put into the air. Putting all the costs together, it became more sensible to encourage people to move into regional and rural Australia and do less commuting.

Meanwhile, Australia’s economic transformation had meant that the knowledge economy enabled that Australians to choose where they wanted to live. Littletown has been recognized as one of the country’s most “liveable shires”

Expansion of the Local Regional City

The local regional city has continued to grow as a population and business centre.

It has become a major transport hub, not least on the new national railway network and the very fast train system. As in the 19th century development of urban locations in Europe and the United States, the creation/ expansion of railway networks created new opportunities for population settlement.

Smart marketing has meant that the large temporary population in the local regional city’s educational and military facilities have been encouraged to see themselves as “goodwill ambassadors” for the region so that they speak highly of their time at the local regional city and they have encouraged others to also visit the area

Entrepreneurial Skills at School

The “Australian Dream” is now to run your own business – rather than work in someone else’s. School students have been encouraged to develop small business skills. Instead of looking for employment as such, they have become skilled at being employable over the long term (such as through periodic training courses).

The process began over two decades earlier with CareerLink, the NSW HSC pathway that gave high school students a head start into their careers and it soon became very popular across Australia. This innovation, along with Australia’s broader economic transformation to exploit the knowledge economy, led to an educational revolution in both schools and higher education.

Schools (including state ones) were themselves eventually run as small businesses and so students absorbed an entrepreneurial culture as they went through school.

This new entrepreneurial spirit flowed over into higher education, when university graduates realized that their degrees provided few opportunities for employment. Higher education became more vocationally oriented, with outside business people and tradespeople having a more direct say in how the institutions were run and what type of education was provided.

Young Australians are working for themselves – and they are doing what they love.

Littletown’s Increased Role in the Service Sector

From around 1847 onwards Littletown’s economic development had evolved down two paths: the creation of the primary sector (farming and occasional gold mining) and the provision of services to pastoralists and miners (such as clothing, medicine and school education).

Regional Australia, home to the farm and quarry – the twin engines that have generated so much wealth for Australians – have been themselves changed by innovation in recent decades. People are still working in both activities but the additional employment opportunities have largely come from the value-added components.

In recent years Littletown – like the rest of Australia – has become a more service-oriented location. While people still need food, the services sector nationally make up about 80 per cent of gross domestic product, with a considerable capacity to diversify Australia’s range of exports. (The total percentage of Australian GDP represented by agriculture is less than 3 per cent).

Littletown’s transformation began slowly and it took some years to notice the extent of the change underway. Here are some examples, not in any order of priority:

- “Retirement migration” refers to the desire of older Australia to travel around the country and perhaps settle in spots they found hospitable. Littletown was one of those spots.

- Littletown’s rural and mining heritage has been exploited via local modern museums and other activities to help older Australians recall the legendary era of the country’s early European development (even if they were city-born and so inventing their nostalgia for a lost era). As the world has became faster and more confusing, so Littletown as a “Rural Sanctuary” offers a haven of peace for reflection and recreation.

- (iii) The Littletown Connection Centre was a national pioneer in assisting dispersed companies enhance the social cohesion between their workers. There is no speed limit on the electronic highway – but people need to know more about who else is driving on it. Not everyone could form their own company (at least at the outset) and so had to work in companies, some of which were geographically dispersed.In the new era, trust became even more important within companies – having confidence in the people with whom one communicated but did not meet regularly around the proverbial water cooler. Therefore, with the growth of “cyber-working” (with employees working for home), companies found that while they saved on expensive city floor space, their employees felt fragmented and isolated.To build company trust, the “company connection” industry was formed so that employees could get together to know each other and “to put faces to names”.Littletown was able to pioneer this work because of its pleasant setting, range of company bonding activities developed by the heritage museums, and access to national transport systems.

- The Littletown Lakeside Health Resort has also done well from health-conscious Baby Boomers. Its innovative “Littletown as Place of Healing” programme has won international recognition.

INDICATORS

- increased economic opportunities

- increased migration into the shire

- more young people opting to remain in the shire

- increased tensions from long-term residents of the shire concerned about the changes to their traditional way of life being brought about by the influx of the newcomers

- Littletown has its third person to reach her 110th birthday

[1] Liza Murray “Remaking Sydney’s Streets for the Modern World”, History (Sydney), June 2006, pp 9-10

[2] Thomas Evans and Thomas S Wurster Blown to Bits: How the New Economics of Information Transforms Strategy, Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000, p 14

[3] Our Future World: An Analysis of Global Trends, Shocks and Scenarios, Sydney: CSIRO, 2010

[4] W Chan Lim and Renee Mauborgne Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2005

[5] Max Hastings Editor: An Inside Story of Newspapers, London: Macmillan, 2002, p 145

[6] Peter Thomson and Robert Macklin The Big Fella: The Rise and Rise of BHP Billiton, North Sydney: William Heinemann, 2010, pp 90-1

[7] Peter Schwartz The Art of the Long View, New York: Doubleday, 1991, p 58

[8] Ibid p 9

[9] Alan Axelrod The Real History of the Cold War, New York: Sterling, 2009, pp 398-402

[10] For example, journalist Bob Woodward has examined how the Bush Administration was unwilling to think about how things could go wrong in Iraq; CIA and other agencies therefore had to tailor their information to fit the perceptions of the politicians: Bob Woodward State of Denial, Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 2006

[11] Wolfgang Kasper, Richard Blandy, John Freebairn. Douglas Hocking, Robert O’Neill Australia at the Crossroads: Our Choices to the Year 2000, Sydney: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980

[12] Keith Suter and Steve England Alternative Futures for Aged Care in Australia, Sydney: UnitingCare, 2001

[13] Linda Belardi “The Great Demise?” Aged Care Insite (Melbourne), August-September 2010, p 6

[14] For example, if I employ a housekeeper (and so pay her a salary), I increase GNP; if I later marry her and therefore stop paying her a salary, I reduce the GNP.

[15] The second largest provider of childcare in Australia are grandparents but they are not paid and so their contribution to GNP is not recorded in the GNP; meanwhile the “costs” of older people are recorded in accounting because of the old age pension and some economists ask “can we afford the elderly” when in fact the older Australians make great contributions to Australia that are not included in the official statistics.

[16] For example, bush fires and other natural disasters are “good” for the GNP because they lead to increased economic activity (emergency services, rebuilding etc).

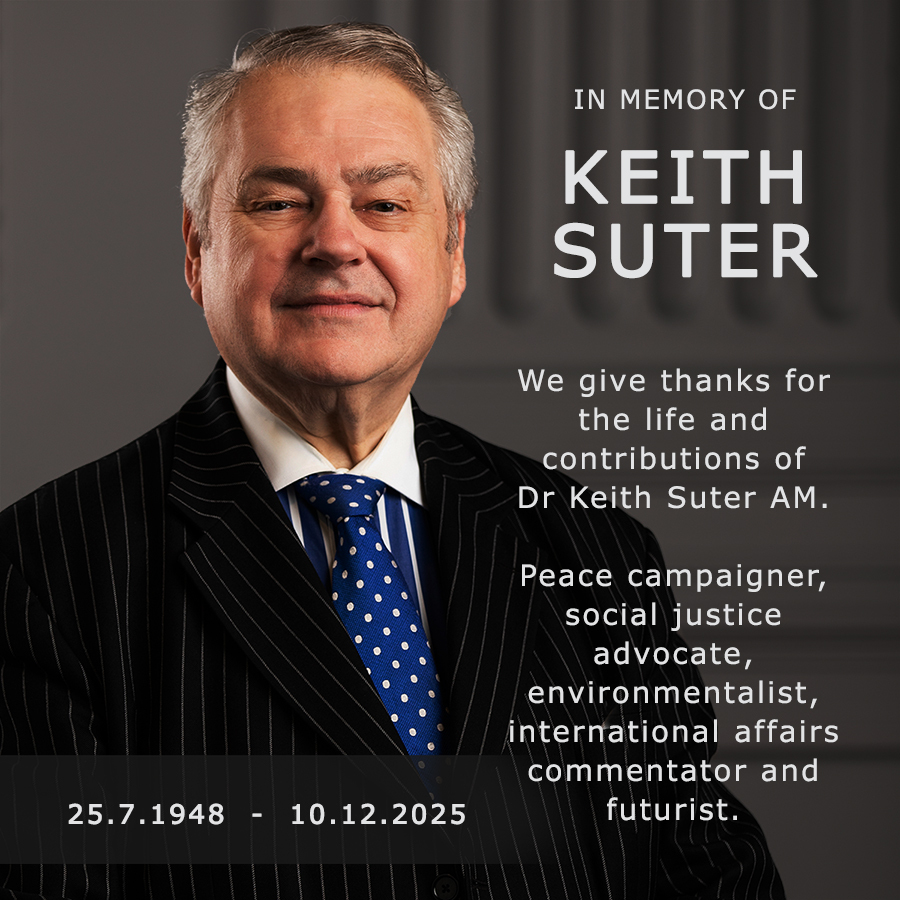

Author: Dr Keith Suter

Managing Director

World of Thinking Pty Ltd