People can look at the same event at the same time and yet “see” different events. We are prisoners of our perceptions. We assume that there is only one way of looking at the world.

A “paradigm” is a way of looking at the world. It filters out some information and focuses on other information. What may be “obvious” to some people is not necessarily “obvious” to others.

“How could they have been so stupid to have done that?” This is a common reaction when looking back upon an event. But to the people involved at the time, it did not appear stupid to them – they were prisoners of their perception. It seemed quite rational to them. Humans will not believe what does not fit in with their plans or suit their own way of thinking.

Scenario planning helps us to rethink our perceptions. It encourages us to think about the future differently.

Scenario planning is the development of a number of stories that describe quite different but plausible futures.

They are “possible futures”. They describe the futures and interpret them. They are not “predictions” – they are not based on extrapolating current trends.

There is no one set recipe. Most scenario planning runs along the following steps:

- Work out the basic issue.Scenario planning is done in response to the perception that there is a “problem” to be solved. It is important that the right initial “question” be identified.

- Understand the organization that has commissioned the scenario planning.How does the organization perceive its business? Why has it decided on that “problem” to be investigated? What is the “official perception” of the future (namely the line laid down by the board or CEO)? How do they see that future changing? What are their hopes and fears? What is its future strategy? What are its stated values?/p>

- Work out the driving forces.The forces can be broadly grouped into five areas: STEEP:

- Social — for example: what are the demographic changes? Australians have gained as much life expectancy in the past century as in the previous 5,000 years: what can they expect in this century? What are the changing expectations that people have?

- Technology — for example: how will the genome project (mapping the body’s DNA structure) impact on medical research? Will that research lead to a genetic engineering revolution so that people could live far longer than at present (say to 200 years)?

- Economic — for example: How will the economy go? Will the gap between rich and poor increase? What will be the impact of the rising giants like India and China?

- Environment — for example: how will “climate change” affect Australia? What old diseases will reappear?

- Political — for example: Will there be an increase in ethnic tensions? What about the risks of terrorism?

- Rank the key factors in order of importance to determine the most important two.The two axes cross each other at their mid-points, creating four quadrants. Conversations with “remarkable people” (or in the Australian style “lateral poppies”) will be useful here. These are people who are outside the current scenario planning project who may have different perceptions from what the scenario planning team may be thinking. They help guard against “group think” and narrow perceptions.

- Work out the Scenario LogicThe drivers are then used as the axes along which the eventual scenarios will differ. These are four different worlds. Create four plausible scenarios.

- Make the Scenarios Come AliveEach scenario needs to be compelling. There has to be sufficient detail in each story to make it easy to follow. A scenario may be uncomfortable but it needs to be believable. Each scenario should have a memorable name.People need to live within each scenario and become fully familiar with it. They will then be well positioned to gauge which of the scenarios is coming into play and have the contingency plans ready. If the scenarios are commissioned by a large organization, then they should be discussed at the various levels of it so that staff can think through what each scenario means for their own area of work.

- Identify the Leading IndicatorsThe future will determine which scenario was “right” in the sense that it was closest to what actually happened. It is important to have indications as quickly as possible which scenario is coming into play.

- Work out the Implications of the ScenariosWe now return to the original problem identified by the organization. What do the scenarios mean for the organization? What are the implications for the organization’s current strategy? What contingency plans need to be in place? What are the options for the stakeholders?

Do Not Argue Over the Value of Each Scenario: Don’t Try to Pick Winners

Finally, one scenario may seem more “preferable” than the others. But scenario planning is not about creating preferred futures. People are welcome to create “preferred futures” (particularly after having their perceptions expanded by a scenario planning exercise).

But creating a preferred future is not scenario planning. Nor should there be arguments over which scenario is more likely than the others. Each scenario has to be equally plausible. Future events will tell you which scenario was “right”.

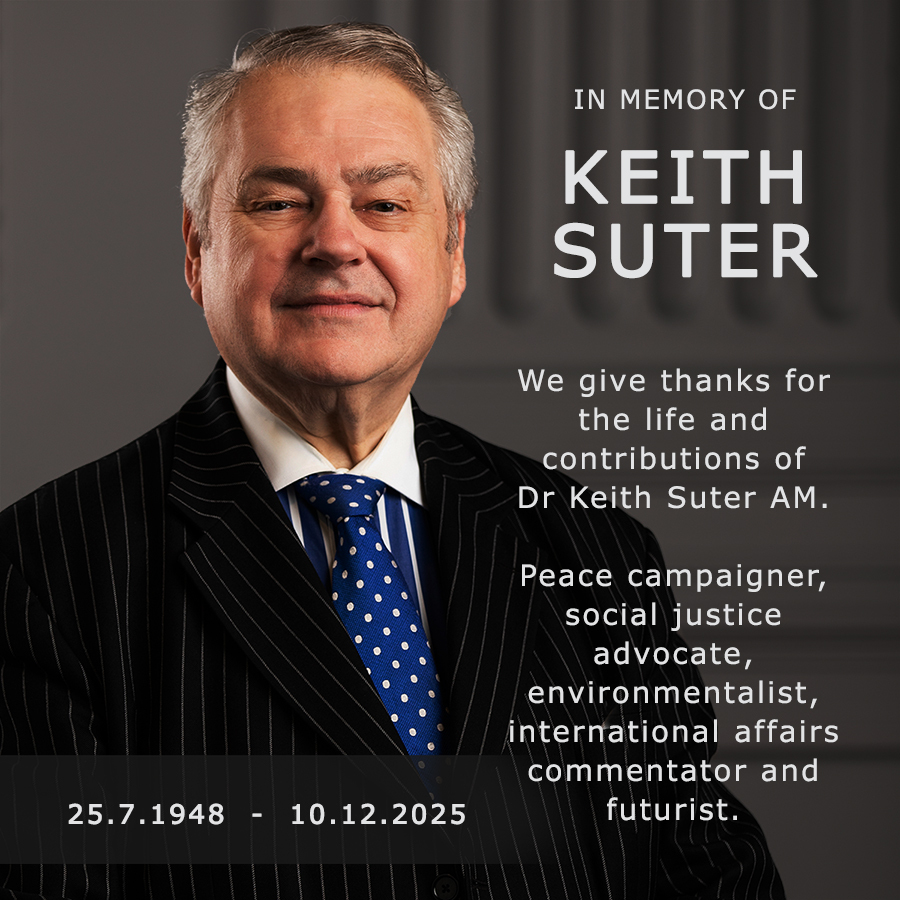

Author: Dr Keith Suter

Managing Director

World of Thinking Pty Ltd